By Alan Ellis and Mark H. Allenbaugh

Click for the PDF version of this article.

INTRODUCTION

According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, federal prosecutions of child pornography possession, distribution and production offenses rose more than 2000% since 1992. This is far and away the fastest growing prosecution rate of any of the major offense categories.

Concurrent with this increase in prosecution has been an increase in potential penalties, both statutory and Guideline. While courts have roundly rejected these new sanctions as politically motivated and lacking empirical support, sentencing in sex offense cases presents unique responsibilities and challenges for which counsel must be prepared.

Who is the average child pornography defendant? Typically, a 42-year-old, white (88.9%) male (98.7%) U.S. citizen (97.7%) with at least a high school diploma (92.1%), though likely at least some college (58.1%), and no prior felony conviction (79.9%). See USDOJ, BJS, Federal Prosecution of Child Sex Exploitation Offenders, 2006 (Dec. 2007). Greater than 95 percent of such prosecutions result in conviction, overwhelmingly via a guilty plea. Id. As is true in most criminal cases, sentencing courts are left to question and understand the factor(s) that contributed to the defendant’s offense behavior, though with sex offenses, recidivism concerns are magnified.

Obtain a Psychosexual Evaluation. One of the first steps defense counsel should take in their cases involving alleged sexual misconduct is to refer the client for a confidential psychosexual evaluation. Similar to a standard mental health evaluation, a psychosexual evaluation assesses an individual’s social, familial, education and employment history, as well as general psychological make-up. However, such assessments focus further on issues concerning sexual history and development, including victimization, paraphilias and risk. Obtaining a psychosexual evaluation early in the sentencing process not only informs issues concerning a client’s alleged misconduct but, looking prospectively, may provide a baseline upon which the client can improve during his/her case’s pendency.

Refer Client for Treatment. Subject to cost and available clinical resources, a recommended course after obtaining the initial psychosexual evaluation, for which a report is not necessary, is to refer the client for treatment with a confidential, independent provider, that is, with a professional other than the person who conducted the evaluation. Stand-alone treatment provides the benefit of enabling the evaluator to view the client both before and after treatment, permitting a more objective assessment of any progress and risk reduction. It also affords additional insight into the client from a second clinician capable of speaking to the evolution of treatment.

Most Lookers are Not Contact Offenders. Courts confronted with an Internet sex offense are generally sensitive to the reality that the step from viewing child pornography to sexual contact is enormous, and there is little-to-no empirical support for a causal link between viewing illegal images and the commission of contact offenses. See, e.g., D.L. Riegel, Effects on boy-attracted pedosexual males of viewing boy erotica, 33 Archives of Sexual Behavior 4, 321-23 (2004). Although, in certain cases, pornography may be part of a larger offense, viewing pornography is not the cause of sexual offending (acting out). See R. Bauserman, Sexual aggression and pornography: A review of correlational research, 18 Basic Applied Psychology 4, 405-427 (1996); W.L. Marshall, Revisiting the use of pornography by sexual offenders: Implications for theory and practice, 6 Journal of Sexual Aggression 1/2, 67-77 (2000). Of particular relevance to federal prosecutions, “the current research literature supports the assumption that the consumers of child pornography form a distinct group of sex offenders.” J. Endrass, et al., The consumption of Internet child pornography and violent and sex offending, 9 BMC Psychiatry 43 (2009).

One study looking at re-offense rates for adult male child pornography offenders found that while four percent (4%) of child-pornography-only offenders (no prior sex offense convictions) committed a further pornography offense, only one percent (1%) escalated to a contact sexual re-offense. M. Seto and A. Eke, The criminal histories and later offending of child pornography offenders, 17 Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 2, 201-210 (2005). Another study found that “there is some indication to suggest that there is a sub group of internet offenders who pose a risk of repeated internet pornography offending, but not an escalation to contact sex offending.… [B]y far the largest subgroup of internet offenders [including those convicted of making child pornography] would appear to post a very low risk of sexual recidivism.” L. Webb, J. Craissati and S. Keen, Characteristics of Internet Child Pornography Offenders: A Comparison with Child Molesters, 19 Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment 4, 463 (2007). Finally, after analyzing six years of recidivism data of 231 men convicted of child pornography offenses, the Endrass study, supra, found:

Among the subjects of the present study, only 1% were known to have committed a past hands-on sex offense, and only 1% were charged with a subsequent hands-on sex offense in the six year follow-up. The consumption of child pornography alone does not seem to represent a risk factor for committing hands-on sex offenses in the present sample—at least not in those subjects without prior convictions for hands-on sex offenses.

When coupled with a psychosexual evaluation that confirms the isolated nature of a defendant’s conduct and low risk to re-offend, the foregoing empirical considerations have contributed to courts regularly rejecting a sex offender’s prescribed guideline range in favor of a more rational disposition, one that satisfies 18 U.S.C. §3553(a)’s parsimony requirement.

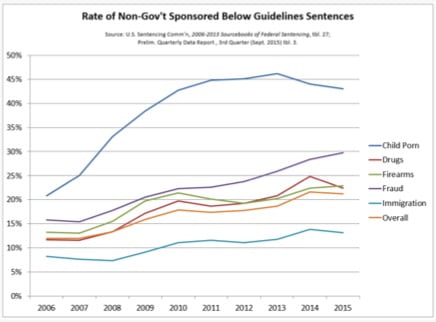

Sentencing Trends. The chart below demonstrates that while, non-government-sponsored below guideline sentences (i.e., non-§5K1.1 departures) have increased across all major offense categories and overall since Booker, the rate in child pornography cases more than doubled from 2006 (20.8%) to the third quarter of 2015 (43.0%), and highest consistently remained the highest among all major offense categories.

Showing Why the Guidelines Should Be Rejected. Key to achieving such a result is clearly showing courts why the child pornography guidelines should be rejected. The person perhaps most responsible for leading this charge has been Assistant Federal Public Defender (AFD) Troy Stabenow. See Mark Hansen, A Reluctant Rebellion, ABA Journal (June 2009). AFD Stabenow’s memorandum, Deconstructing the Myth of Careful Study: A Primer on the Flawed Progression of the Child Pornography Guidelines, provided the analytical framework on which first district courts and then circuit courts relied when holding the sex offense guidelines unsustainable, on policy grounds. See United States v. Henderson, 649 F.3d 955, 962 (9th Cir. 2011) (most amendments to the child pornography guidelines “were Congressionally-mandated and not the result of an empirical study”); United States v. Grober, 624 F.3d 592 (3rdCir. 2010); United States v. Dorvee, 616 F.3d 174 (2nd Cir. 2010).

Equally as important, the Sentencing Commission effectively corroborated Attorney Stabenow’s conclusions concerning the guidelines’ deficiencies through its own report and analysis. USSC, The History of the Child Pornography Guidelines (Oct. 2009). In 2012, the Commission published a comprehensive follow-up report to Congress entitled Federal Child Pornography Offenders that further corroborates its earlier findings and documents the continuing dissatisfaction the judiciary has with these Guidelines.

AFD Stabenow’s article has been cited by federal district and appellate courts dozens of times since its initial publication. It also has been cited in dozens of law review and law journal articles. A version of AFD Stabenow’s original white paper was published in The Federal Sentencing Reporter, considered by many to be the preeminent journal on federal sentencing matters. See A Method for Careful Study: A Proposal for Reforming the Child Pornography Guidelines, 24 Fed. Sent. R. 108 (2011). The U.S. Sentencing Commission also cited AFD Stabenow’s original white paper in its ground-breaking Report to Congress on the Child Pornography Guidelines. See U.S. Sentencing Comm’n, Federal Child Pornography Offenses at 2, n. 15; 3, n. 71; App. G at G-4 (2012).

*This article is adapted from the Alan Ellis’ Federal Prison Guidebook. Next month, the Alan Ellis Update will feature Part 2 in this series: Sex Offenders: Prison.